Closing the lending gender gap

To make our economy truly financially inclusive, there are many things we need to address – from ensuring people are paid equally to removing biases from the financial ecosystem. One of those biases that urgently needs to be tackled is in the lending market, to ensure that women are not disproportionately prevented from accessing credit and financing products.

Women are key contributors to the economy, making up 40 percent of the world’s workforce – particularly in developing economies. Not only are women typically responsible for the bulk of household purchasing, but their employment falls in sectors that are crucial for economic growth and development.

That said, we often find that women’s involvement in the flow of capital around the economy to be less than we might expect – with reasons stemming from cultural barriers to participation to structural issues in the financial ecosystem. While cultural issues may be more difficult to overcome, there are things we can be doing to address these structural issues holding back the female economy.

The credit industry, from regulators to lenders and to credit bureau all contribute to make changes. In this article, we discuss some of the challenges of the current situation to some of the potential solutions.

In some markets, the gender pay gap is particularly pronounced – a Creditinfo analysis of the Lithuanian market found that of the 81 sectors into which economic activity breaks down, men are paid more than women in 72, and average pay for men often exceeds women by 30-50 percent. In some sectors, such as air transport, gaming, and gambling, men’s pay can be up to 127 percent above their female colleagues. Closing this gap is going to be key to rebalancing the economy and realising a more financially inclusive world. There is work being done as part of the ESG initiatives (ESG = Environmental, social and corporate governance) that is starting to make salary gaps more transparent, as well as representation of women on company boards. Credit bureau, such as Creditinfo Lithuania, are providing specific segments on credit reports to ease access to this information.

However, even outside of pay issues, there are significant problems in the lending markets – and here data can help provide a way forward.

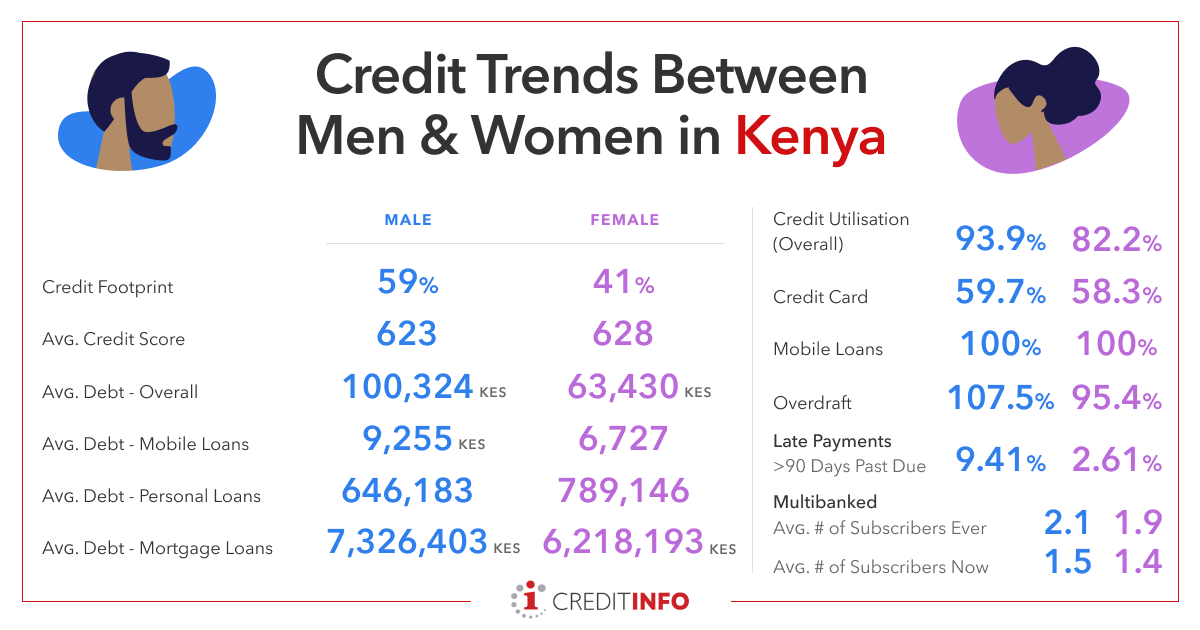

Creditinfo analysis of the lending market in Kenya yielded some very interesting findings. Despite women having higher average credit scores than men (628 vs 623), they have significantly smaller credit footprints (41% vs 59%) and utilisation (82.2% vs 93.9%). This is quite a marked difference and can have a widespread adverse impact.

If women are not able to access financing on a personal level, then their spending power is diminished and their non-participation in the economy will be felt. If they are not able to access financing on a professional level too, the effects are compounded – and the economic imbalance will continue to hold back economic growth and development.

Many other developing economies are experiencing the same issues. In Morocco, for example, the lending market similarly favours men, with women only making up 31% of the active borrowing market.

This needs to change.

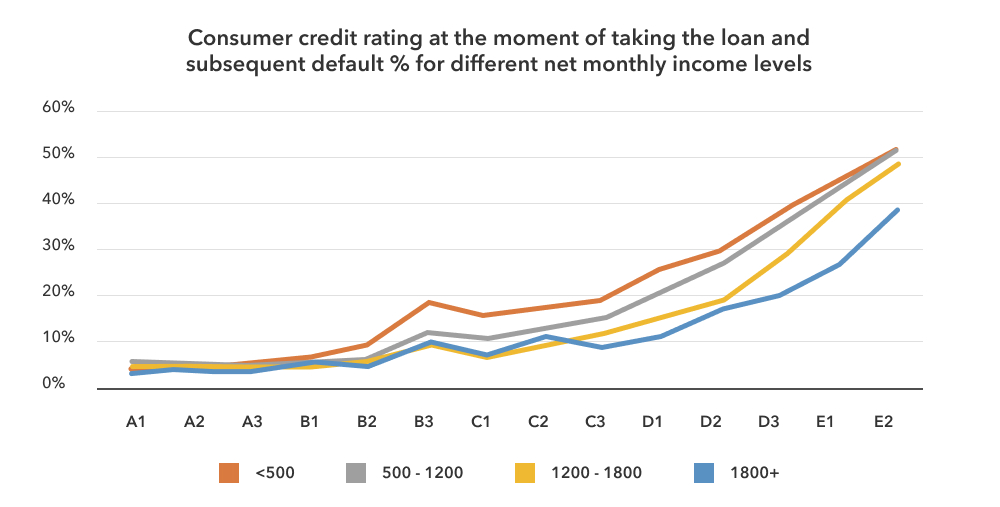

To make our world fairer and our economy work for everyone, we need to remove these structural barriers to financing. In general moving to digital lending and minimising subjective human intervention in lending vastly improves the equality. Credit scores will reflect the actual risk of individuals based on actual data. It is important that historic bias is not built into algorithms, model developers need to be aware of the potential of this and remain vigilant.

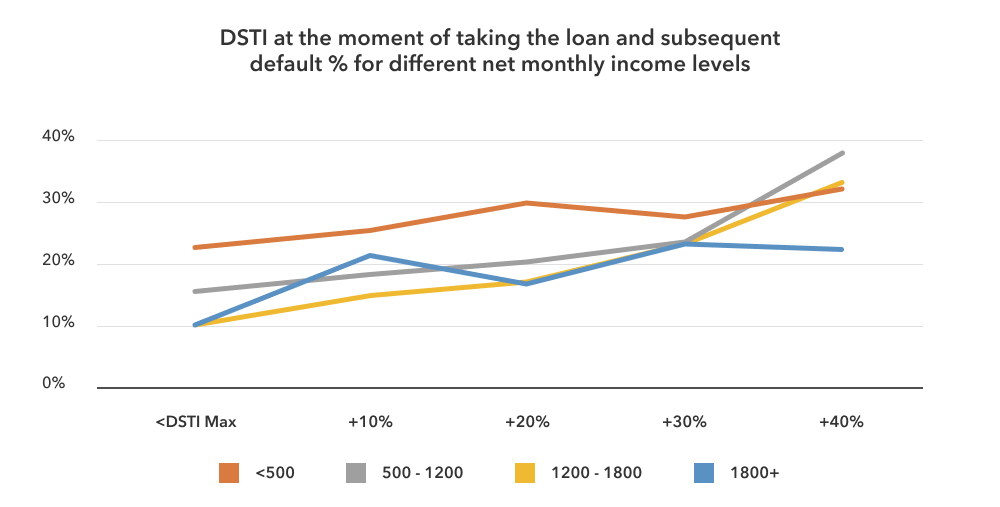

Regulators have a role as well, over dependence on DTI (debt to income) in their supervisory rules can build in a strong gender bias. The evidence has already been shown that women are lower paid. With DTI rules, large proportions of women can be forced to high interest rate lending or pushed out of formal market to the informal credit market without legal protection.

We see the evidence from Latvia where the credit score (fig 1) is highly predictive of future non-payment and should be a significant element of credit decision, it is proven to be predictive at all income levels. DTI ( Fig 2) is much less predictive and would eliminate many lower income women from formal credit where strict rules around DTI exist.

The best way to start making changes is by using data, whether ESG information or credit scoring. If we can understand the situation clearly and how the picture needs to change, we can begin to address it. We can also measure and manage progress against key performance indicators.

For lenders, this can be a significant opportunity – that a whole section of the economy, with good credit scores and low credit utilisation has been continually underserved, means they can be very targeted with new products and services that cater to that nascent market and generate new revenue streams while tackling financial inclusion.

This is something we believe very strongly in and are working with partners to help address. If we can help de-risk the lending ecosystem, we can make the economy fairer for all and reap the significant benefits that unlocks.

Visit www.creditinfo.com for more information.

Emma Camilleri,

HR Director, Creditinfo Group.